How We Stay Warm and Keep Cool

An Update on

Buildings

If you only have brain space for three things

Buildings last a long time. The ones we build today will likely still be emitting carbon dioxide (CO₂) long after we’re gone. As we noted in the steel/cement chapter, it takes a lot of carbon to construct them. But it also takes a lot to operate them. That’s why we need to make them far more energy efficient and electrified.

Cooling demand is rising rapidly. Of the five billion A/C units expected to be in operation around the world by 2050, roughly 40% have already been installed. We have the technology to decarbonize this boom by using more efficient A/C units and heat pumps, plugging leaky ducts, and changing out single-pane windows, but mass deployment is a challenge. Buildings waste a lot of energy.

Going forward, behavioral changes will be key to decarbonizing this sector. The technology is here and the Green Premiums are lower than for other grand challenges. Now we need governments, corporate buyers, and other consumers to buy in.

Old Buildings,

New Ideas

1

1

An old brownstone in New York City

The median age of a building in New York City is 90 years old. In Europe, over 85% of today’s buildings will still be standing in 2050, and the majority were built before energy efficient standards existed. Point is, buildings last a long time.

The buildings our grandparents constructed are still emitting CO₂ today. And the ones we build today will likely keep emitting CO₂ long after we’re gone.

What’s more, the updates we make to buildings rarely make them more efficient. In Europe, for example, 10% of buildings are renovated every year. But only one percent of those renovations have a positive impact on the building’s energy usage.

This is a major climate challenge. Buildings account for seven percent of global emissions, and that’s just measuring on-site energy usage. Taken together with source energy (i.e. the total amount of raw fuel needed to operate buildings, including transmission, delivery, and production losses) and embodied carbon, they account for approximately 40% of global CO₂ emissions, which makes buildings the largest contributor of all the sectors we’ve discussed.

But since we’ve already covered the majority of embodied CO₂ emissions caused by using cement and steel in building construction, we’re going to focus this section on the carbon footprint of operating homes and buildings.

Through air conditioners, furnaces, and water heaters, heating and cooling today’s buildings consumes a lot of energy and emits a lot of CO₂ in the process. Buildings also waste much of the energy these devices produce. Our structures are essentially leaky containers, filled with single-pane windows and uninsulated, leaky ducts that let energy out. In fact, as much as 40% of heated or cooled air leaks out of the typical building.

Here’s the good news: Compared to some of the other sectors we’ve discussed, the technologies we need to decarbonize heating and cooling already exist for the most part — from heat pumps and smart controls to energy-efficient air conditioners and double- or triple-glazed windows.

The main issue is deployment.

We’ve already built a lot of buildings, and as we’ve discussed, they last a long time. It’s going to take a colossal effort not only to update the way we construct our homes and offices, but to retrofit the buildings we already have to make them more energy efficient. We need to update building regulations to allow for the use of new materials and processes, and encourage building and home owners to make the changes needed.

Everything Under Control:

Raising a

Commercial

Building’s IQ

2

2

A green building facade

In 1999, Disney released an original film called Smart House about a futuristic home that develops a mind of its own, with controls for everything imaginable. Sentient homes that turn evil aren’t quite what we’re going for, but building automation is a key piece of the decarbonization puzzle. Because the better you can control a building’s energy usage, the better you can limit its emissions.

That’s the idea behind companies like 75F , which is working on advanced building controls for small-to-medium sized buildings that often get overlooked by automation advances. We know that building intelligence can have a major impact on efficiency.

We’ve already seen this progress in other areas of our lives. For example, when you get in a car these days, there’s a button, lever, or dial at your fingertips for just about everything: A/C, seat-heaters, defrost, music, GPS, gas levels. Buildings should be the same. There’s no reason a four-story condo building should have fewer controls than a two-passenger car.

Keeping Our Cool

Innovations for the Coming A/C Boom

3

3

Extreme heat is accelerating the A/C boom, creating a vicious emissions cycle

One of the most frustrating paradoxes of climate change is that, as the world gets hotter, our main method of cooling down could make climate change even worse.

Not only do air conditioners increase CO₂ emissions, they also leak an even more harmful substance: refrigerants. Known as F-gases, refrigerants cause thousands of times more warming than an equal amount of CO₂.

We have to break this vicious cycle, because the demand for cooling isn’t going anywhere but up. Global heating demand is nearly 30 petajoules per year. To put that in perspective, that represents more than 780,000 years worth of electricity for the average American home. But cooling is projected to surpass it before the end of the century.

More than 90% of American homes already have an air conditioner, compared to just 12% of homes in India. But as temperatures in already hot places like India continue to increase, more people will want access to air conditioning. By 2050, there will be more than five billion A/C units in operation around the world — more than twice the amount in use today. Air conditioners will consume as much electricity as all of China and India do now.

Several companies are exploring ways to meet this cooling demand in an energy efficient way. Take Blue Frontier , for example, which has developed a liquid desiccant that behaves like a battery for your air conditioner. Blue Frontier uses this liquid desiccant to store energy as “dehumidification potential.” Combined with evaporative cooling, their technology can pull moisture out of the air in your home and make it cooler. This not only cools your home without the use of harmful refrigerants, but it also reduces peak energy demand by allowing you to store electricity at its cheapest and deploy it when costs are high.

The technology was actually first discovered as a way to kill anthrax, not unlike the original concept for air conditioning, which was developed as a (misguided) way to treat malaria.

Blue Frontier is just one example of several companies working to revolutionize the air conditioning space. enVerid is another innovator in this space. enVerid’s solution pulls CO₂ and other gaseous contaminants out of indoor air, which allows you to recycle more air and lower the load on your A/C. This especially helps in hot summer and cold winter months; it also allows you to use a smaller A/C unit.

But even as these technologies get better, consumers aren’t taking advantage of them. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), the typical A/C unit sold today is only half as efficient as what’s widely available. That means they either don’t have the information or the incentives to make energy efficient choices. We need to change that.

Some Like It Hot

Why Heat Pumps

Are Key to

Decarbonization

4

4

Even as temperatures rise, winter is still coming. And just as we’re exploring ways to cool down our homes without warming our planet, we also need clean and efficient ways to stay warm when things get frosty.

Today, furnaces and water heaters account for a third of all emissions that come from the world’s buildings. And unlike A/C units, they don’t all run on electricity. They’re typically powered by oil, natural gas, or propane, which means just cleaning up our electricity grid won’t solve the problem.

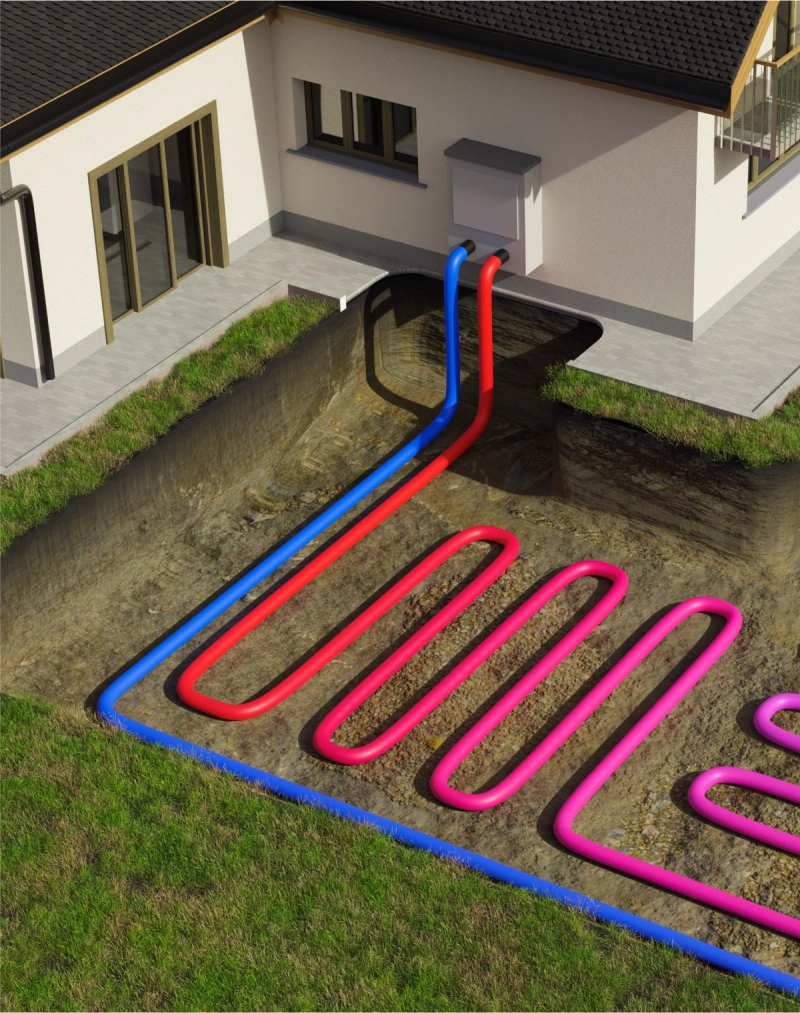

An illustration of a ground-source heat pump system using geothermal energy

That’s where heat pumps come in. Because heat pumps run on electricity, they move us away from needing fossil fuels to heat our homes.

There are many different heat pump designs, but the process is similar in all of them: transferring heat from your home to an outside source to cool it down, or transferring heat from the outside source into your home to heat it up. It’s the source that changes from design-to-design. For example, air-source heat pumps use the air outside your home. Air-water pumps use reservoirs of water with steady temperatures.

A company called Dandelion uses a powerful geothermal heat pump to replace your home’s entire HVAC system. This heat pump takes advantage of the stability of the Earth’s temperature ten feet underground, which remains 55 degrees Fahrenheit during both winter and summer. During the warmer months, the heat pump takes heat out of your home and puts it in the ground. Once winter rolls around, it takes heat from the ground and puts it back inside your house.

Heat pumps aren’t without their flaws. For example, they struggle to operate at full capacity in extremely cold weather. But they have improved enormously in recent years.

400m

30 years ago, heat pumps were only effective down to about 32 degrees Fahrenheit, or freezing. Today, we have heat pumps that are effective at -15 degrees Fahrenheit. Despite this progress, we still have work to do. And we’ll need continued heat pump innovation and other solutions, like e-fuels, for areas of the world where heat pumps aren’t fully effective. Nevertheless, heat pumps will be a key piece of the decarbonization puzzle. In fact, we need an estimated 400 million more heat pumps installed this decade to reach our net-zero target.

A geothermal heat pump

A company called Conduit Tech is trying to fix this bottleneck by streamlining the ordering and installation process. Conduit enables HVAC professionals to more easily identify homeowners that are good candidates for electrification and support them through the product lifecycle — design, installation, and maintenance.

30%

The recent Inflation Reduction Act is helping, too, by heavily subsidizing heat pumps, with tax credits up to 30% of the purchase cost.

Window of Opportunity

Breaking Up with

Single-Pane Glass

5

5

Look out your window and you’ll see another way your house may not be as efficient as it should be. No, we’re not talking about what you see from the window. We’re talking about the window itself.

An open window looking out at the countryside on a foggy day

The window glass in most of the world’s homes and buildings is single-pane, which means a lot of the heat from your house is leaking out, forcing your HVAC system to work harder, cost you more money, and emit more CO₂ into the atmosphere.

In fact, windows are the number one source of heat gain in the summer and heat loss in the winter.

Facade of a glass skyscraper

LuxWall

is trying to change that with an incredibly efficient next-generation window. It consists of two specially coated glass panes with a vacuum between them, and it retains four times as much heat as a single-pane window. Think of it like the insulated coffee mug you use in the morning. It keeps things warm on your way to work a lot better than the average cup.

These windows also don’t require a lot of installation labor. Without even taking apart your window frame, an installer can switch out three of your single-pane windows for double-pane ones in the same time it takes to bake a frozen pizza.

As with heat pumps, the challenge here is mass deployment. The world currently has 17 billion square meters of single-pane windows. In South America, Africa, Australia, and much of Asia, more than 80% of windows are single-pane.

Replacing all those windows is a daunting task, to say the least. But it’s more than worth it. Because as long as we continue to use single-pane glass, we are quite literally throwing energy out the window.

Duct, Duct, Loose

Sealing

Your Home

6

6

A one-story home

Another way your home is losing energy is through what developers call a “leaky envelope.” In addition to windows, your home often has loose ducts and cracks in the walls that allow air to leak out.

Plugging these leaks can help lower energy usage and save you money on your next energy bill.

Aeroseal is shrinking carbon emissions from residential and commercial buildings

A worker installing a vent duct

Aeroseal , an Ohio-based company, deals with all the air leakage not involving windows. They’ve developed a harmless polymer fog that’s light enough to float in the air. To seal up a building, they close all the doors and windows, blow air into the building to raise the pressure inside, and then release a fog of these polymers. As the air heads for leaky spots in the air ducts and walls, it carries the polymers, and they build up in the cracks and crevices, making them air-tight.

This can be done at a fraction of the cost — and time — of the traditional manual process. And thanks to deals with several large homebuilders and developers in the United States and Canada, Aeroseal has already sealed over 250,000 buildings.

A flower box outside a home with cracks and peeling paint

Unfortunately, sealing your ducts and updating your HVAC system just isn’t as sexy to homebuyers, renters, or real estate agents as redoing your kitchen or adding an extra bathroom.

Right now, it just doesn’t affect the home value as much. As we’ve seen with the other grand challenges, many of the necessary changes don’t affect comfort, quality, or functionality for the consumer, so it’s difficult to convince them to accept the Green Premium.

What’s more, there’s a split incentive problem at play when it comes to big apartment complexes and commercial buildings: If the renter is paying the electricity bill, the landlord has little incentive to retrofit the building with more energy efficient appliances, such as an improved HVAC system or better-insulated windows. These behavioral challenges are at the core of the decarbonization challenge in the buildings sector.

So this will be an uphill battle, but the technology is already here. The Green Premiums

are lower than for other grand challenges, and in some cases even negative. And the impact on our climate could be a game-changer.